Just came from watching Marvel’s Black Panther. The buzz on the Internet has some saying it’s the best Marvel movie ever, some not very happy with it. I personally think it’s a great movie, not quite as entertaining as the other Marvel movies, particularly the best of the recent crop like Civil War, Spiderman: Homecoming, and Thor:Ragnarok, but far deeper and loaded with social commentary. It’s possibly the opposite end of the spectrum from Thor:Ragnarok, a candy-floss light flick full of jokes. In Black Panther’s case, the humour is kept low, due to the sensitivity of the subject matter. But what it lacks in laughs, it more than makes up in heart.

From this point onwards, there’ll be SPOILERS, so if you haven’t seen the movie, you should bookmark this page and come back later when you’ve finally caught it.

The movie works for me on many levels.

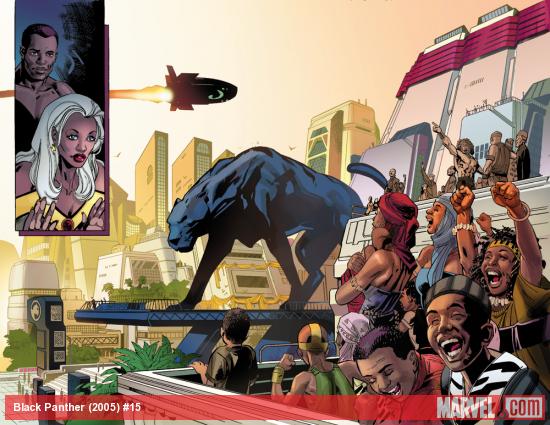

As expected of a Marvel movie, the special effects are tremendous. It is first and foremost a superhero movie, so it doesn’t disappoint in the action. Wakanda itself is portrayed as a high-tech city hidden behind a cloaking device, and what we see of it is impressive. Unfortunately, due to constraints about the movie length, we don’t get to see more than what was hinted at. But even then, the tech is way beyond what the rest of the world has. It rivals even the best of what Stark and SHIELD can offer: cloaking tech, hover tech, beam weaponry, energy shields, concealed weapons that can grow into full-sized spears, and more. The only strange thing is that while the elite soldiers in Wakanda get beam weapons or things of the like, Black Panther himself is armed only with claws. It’s a narrative that works for comic books, but realistically, if he’s the king and protector of his people, it would make sense to give him a couple of plasma cannons up his sleeves as well, or at least one of those killer spears that shrink to the size of a mobile phone (presumably). But, those are minor complaints.

The movie makes the effort to humanize the villain – which is something good storytellers do. Pixar is a master at it – the villains usually have some understandable motivations for their behavior (see the bear in Toy Story 3, or Syndrome in the Incredibles). In some Pixar movies, there aren’t even any real villains at all – see Cars 1, or Inside Out.

Marvel has done well in showing that not all villains are evil – some are simply misguided, and some act out of a deep pain and bitterness.

For me, the best Marvel movie so far was Captain America : Civil War. While it was like a mini-Avengers with so many heroes in it, what I loved most was the fact that the enemy of the Avengers was not an army of identical looking aliens/robots/creatures, but each other, in a way. Conflicting ideologies and the way to resolve them have been at the root of many of the worst wars in human history – land grabbing and world domination have not always been the cause. In Civil War, the trigger for this clash of philosophies was actually a man, not a supervillain like Loki or Thanos. And not just a cookie-cutter villain – a man driven by a deep hatred and anger, having lost his entire family in Sokovia because of the actions of the Avengers and their creation – Ultron. This made the movie much richer and believable, and Black Panther follows a similar path. Interestingly, Black Panther himself was introduced as a character in the MCU in Civil War.

Black Panther’s main villain (I would say Ulysses Klaue is a secondary villain) is given similar treatment – his motivations are clear, understandable, even, because of what happened to him and his father.

Killmonger is driven by a mixture of (i) anger and sorrow from losing his father when he was just a small boy (ii) feeling abandoned by his father’s community (which he found out about through the book) and (iii) a general sense of injustice about how black people have been treated over the years, especially while Wakanda sat by and did nothing. While his actions and behavior are reprehensible, one cannot help but feel a bit of sympathy for how he ended up there. And the director, Ryan Coogler, makes the effort to show this journey – by giving Killmonger his own scene with his father just like T’challa had. And even the confrontation between Killmonger’s father and T’chaka was played to show that neither was entirely right or entirely wrong – the choice between protecting your people (as defined by your country and kingdom), and protecting your people (as defined by Africans in general, including those in America descended from former slaves).

What is actually interesting is that the child version of Killmonger doesn’t cry for his father’s death, but instead says “everybody dies, it’s just the way it is around here.” That in itself, is a social commentary about the violence on the streets of inner city America. But the older version of Killmonger sheds tears for his father, and it is this reversal that is most effective – a kid growing up in a tough neighbourhood, shrugging off death like it was an everyday occurrence, and a grown-up, highly trained fighter with dozens of kills to his name, crying for his own late father. It’s a beautiful moment, and gave the movie a lot of depth.

African culture is portrayed respectfully and in detail. The movie goes to great lengths to try to show how an advanced African nation might integrate technology with ancient traditions. The spears carried by the elite guard are not just ceremonial – they are made of vibranium and have immense destructive potential. The ceremony for crowning a new king is a mix of ancient and modern practices, and the Wakandans do not shy away from using their tech for missions that they deem important for national security. The diversity of Africa and its tribes, along with the great outdoors, is captured for all to see, without being too preachy or slow-paced. Much of it, of course, is from the original comic book source material, where an African nation is the world’s most advanced nation, and way ahead of the rest of the world in many areas. Nonetheless, to flesh it out visually in a movie took some skill, and I think the director did a great job.

Finally, the wider social commentary about slavery and the oppression of black people is handled tastefully. This is the core of the story – what drives the plot. The subject matter is highly sensitive – even today, racism is a very hot potato of a topic, and between #blacklivesmatter and the allegations of police brutality and discrimination against minorities (specifically those of African-American descent), this issue is still very much live and in the balance. While Trump’s racist rhetoric seems aimed mainly at Latinos and illegal immigrants from the Middle East, in truth, his ignorant views attract a lot of support from white supremacist groups, for whom black people in America are equally unwelcome.

This has been the greatest tragedy of America – from its founding till today, it has never fully shaken off its painful past. Slavery may have been abolished a hundred and fifty years ago, but racism in many forms persisted even up till the seventies, where whites and blacks went to different schools and sometimes different washrooms in the same school. “Segregation” stayed around far longer than “slavery”.

Black soldiers were kept separate from whites during World War 2 – it was only in Vietnam that integration began to really happen. In view of all this, the movie could have been one long angsty diatribe – how whites have oppressed blacks for years and now is the time for revenge.

Instead, it takes a much more nuanced and balanced view. In fact, the main villain is driven by precisely this dangerous mindset – that black people need to rise up and be the new oppressors instead. The opening sequence, set in 1992, shows two black men plotting something which looks like an armed robbery. It could just as easily have been an assassination plot, or an act of terrorism. They are later revealed to be Wakandan spies, though one of them did not know this about the other. The movie makes it clear that violence is not the solution, that death only begets more death. T’challa recognises this – in fact, the movie repeats the line many times, that using superior technology to kill others is not “the Wakandan way”. Thus, while the movie takes a sympathetic lens to the injustices that the black community were subject to, it does not veer to the extreme where the answer is to respond with “an eye for an eye”.

Furthermore, the actions of the Wakandan kings over the years are also portrayed as contributing to the problem – it is the reason why T’challa, previously so respectful of his father and ancestors, makes the angry statement that they were all wrong. The bigger social commentary is that those who know injustice is being done, but do nothing, in order to protect themselves, are at some level to be blamed as well. And while the culpable in the movie is the kingdom of Wakanda, it can be argued that anybody in the real world who deliberately turns away from those in need is guilty of this.

The movie ends on a melancholic note – while we cannot erase the past, we can choose to live differently. T’challa is told this – that he should not hold himself responsible for the actions of previous kings, but must now choose what kind of king he wants to be.

The whole story is wrapped in an elegant manner – the final scene of Killmonger’s death.

At this point, he utters a great line, which I love. He says that he chooses to die rather than be imprisoned in Wakanda, and asks that his ashes be scattered in the ocean. He then says that he will join his ancestors, who jumped off the slave ships bringing them to America, knowing that they would drown in the ocean, because they felt that death was better than bondage. That the ending is played so slowly and dramatically shows that the director is intent on driving home the message – that the choices facing many black people are stark and painful, and lead to desperate acts. In fact, much of the inner city crime on American streets is precisely because of the lack of good choices for the poorest of the urban poor. The cycle of poverty has to be broken, otherwise it leads to generations of crime borne out of desperation.

This is just a movie, at the end of the day. But sometimes, it takes seeing something like this, not a scathing commentary, but a carefully crafted tale of sadness and choice, that hopefully makes us all more conscious of our own shared humanity with others, who may not share the same skin colour as we do.

Let’s take to heart the message of T’challa at the movie’s end:

“We must find a way to look after each other, as if we were one single tribe.”